JTMH Volume 23 | Before the Armadillo

Local Memory: Music in Austin before the Armadillo1

Michael J. Schmidt

“Local Memory: A History of Music in Austin” is a digital public history project by Brian Jones and Michael Schmidt.

Brian Jones and I first began discussing Local Memory at the end of graduate school. At that moment in 2014, we were, in many ways, pointed in the same direction. Although Brian and I both had decided to not pursue traditional academic teaching careers, we were enthusiastic about continuing some of the digital humanities collaborations we had started in the online journal The Appendix.2 Finding a new subject was fairly easy. We simply picked up a topic we had already spent hours talking about over the previous five or six years: Austin’s music history.

We were certain that we wanted to make it a digital project and were intrigued by the possibilities a website could offer for experiments in form and content. Where to start was less obvious, however. Ultimately, we decided to first explore the periods about which we knew the least. Most scholarship on music in Austin has focused on the last third of the twentieth century, although important work has been done by Michael Corcoran, Margaret Moser, and Richard Zelade on the preceding decades.3 By looking at the interwar and immediate post-war eras, we hoped to illuminate some of the elements that fed the remarkable cultural bloom in Central Texas that began during its countercultural moment.

Thus, Local Memory’s first two online exhibits point to a somewhat forgotten period in Austin’s music history: the years between the onset of the Depression and the beginning of rock and roll. For most listeners, these are likely unfamiliar decades. The 1970s have long dominated Austin’s musical identity, endowing the city with a reputation for non-conformity in a sea of traditionalism.4 By Ronald Reagan’s second term, the Texas capital was synonymous with outlaws and outsiders, hippies and intellectuals, much of it driven by musicians and venues like Willie Nelson, Doug Sahm, Townes Van Zandt, Antone’s, the Soap Creek Saloon, and the Armadillo World Headquarters.5

The powerful legacy of the 1970s, however, has obscured the ways that Austin was already a unique musical place before the advent of the cosmic cowboys. Local Memory shows that it already stood culturally apart from Texas’s other major cities during the first half of the twentieth century, albeit in a way remarkably different from its later reputation.

Roughly spanning from 1929 to 1955, Local Memory’s current exhibits document two thriving local music scenes that emerged during these years. The first, “Athens on the Colorado,” focuses on dance orchestras at the universities while the second, “The Rise of the Honky Tonks,” covers small vernacular pop bands in working-class dance halls and bars. Together, these scenes embodied what made the capital a distinct musical environment in the decades before the 1970s: Austin was remarkably in sync with the national music industry in a state producing a staggering number of regional innovations.

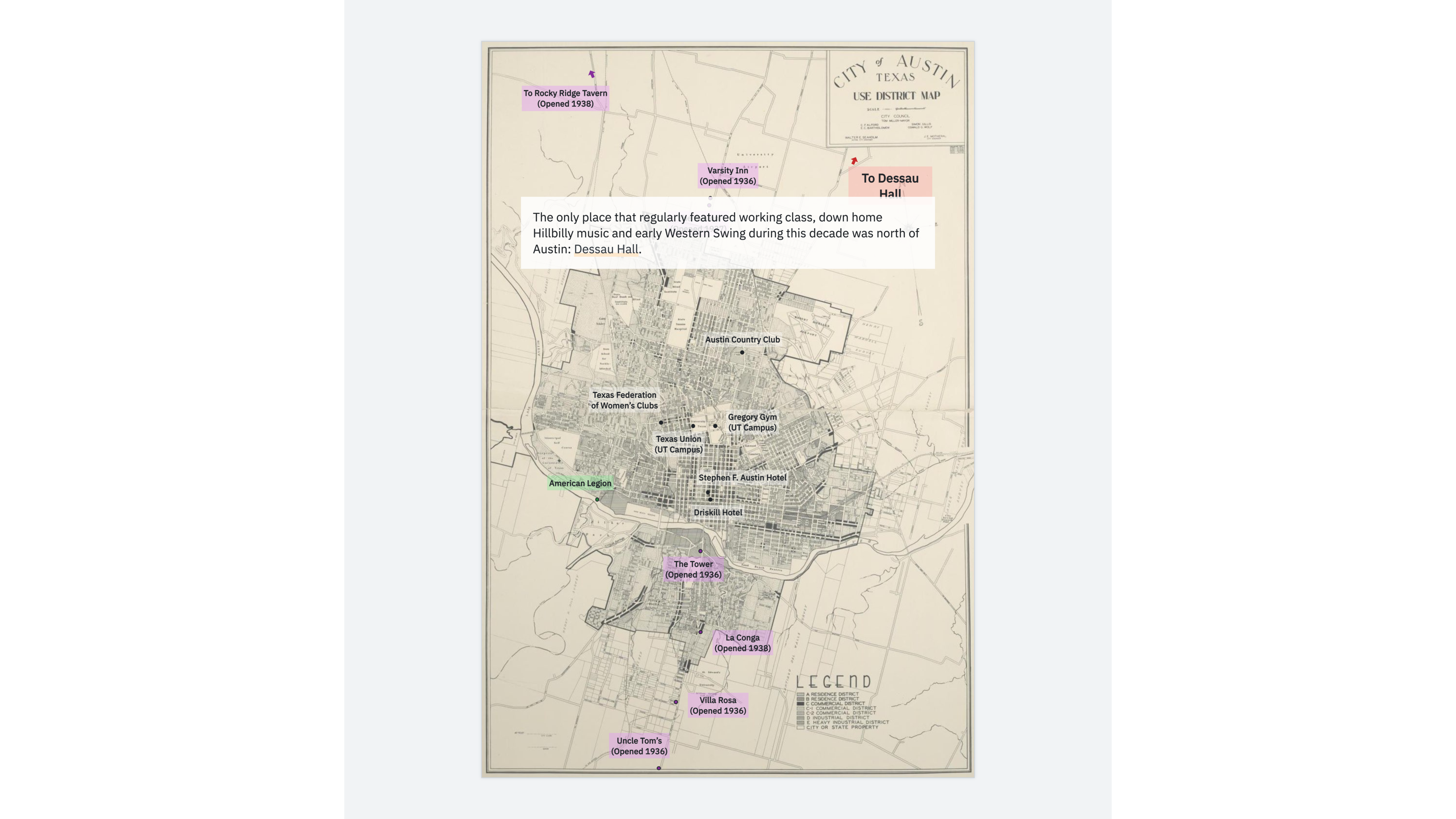

Local Memory tells this story as much with images, maps, graphs, primary documents, oral histories, and music recordings as it does with text. A website instead of a book or article, it gives readers/listeners the chance to hear Nash Hernandez discuss his father’s life and band; see the economic disparities between Black and white musicians in Austin through data and graphs; read a 1938 article in the Daily Texan explaining jitterbugs; track the growth of honky tonks between 1935 and 1950 through interactive mapping; and take in the ambience of Depression-era UT dances through a photo essay. Local Memory attempts to create a polyphonic narrative: to not only include the voices of other authors and participants, but to do so through many forms of information.

Local Memory’s multimedia content shows that, if Austin became intractably linked to folk-affirming, intellectual, and outsider music in the late twentieth century, it stood out as the most pop-centered city in Texas in its earlier years. Instead of bucking the trends of the music industry, it was more deeply attuned to them than any other city in the region. At a time when musicians in Dallas, San Antonio, and Houston were creating the distinctive regional styles of Western swing, honky-tonk country, conjunto, orquesta music, and early rock and roll, Austin did the opposite: it closely followed the broadest forms of national popular music.

This is most clear in the music of the 1930s and early 1940s, the subject of the exhibit "Athens on the Colorado: The Rise of the Universities." Although forgotten now, Austin was a major hub for big band music during the height of its New Deal popularity. This might seem surprising for a small city that was geographically and culturally far removed from the film industry, recording studios, and Tin Pan Alley on the East and West coasts. Austin’s large student population and the growing resources of its colleges, however, helped ensure that its musical life was far richer and more prestigious than other Southern and Southwestern towns its size.

College students’ money and taste dominated Austin’s commercial pop music world throughout the 1930s and early 1940s. This demographic gave the city a unique musical profile in Texas during the period. Although vernacular musics, like fiddle tunes and barrelhouse blues, were certainly present and beloved by their listeners, Austin’s live music world was overwhelmingly characterized by modern dance orchestras. The highly arranged swing and “sweet” music of these bands was the hallmark sound of the national industry at the time, the essence of mass-marketed and large corporate trends. This mainstream orientation distinguished Austin from the music scenes of other Texas cities, where national big band styles were played at dance venues and hotels but existed as a small part of a larger panoply of local styles.

The University of Texas's growing student body and oil wealth made Austin a consistent destination for now legendary orchestras of the era, like those of Louis Armstrong, Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, Guy Lombardo, and Dizzy Gillespie. At the same time, the constant appetite for dancing from the students, clubs, and fraternities/sororities created a foundation for the city’s first sustained ecosystem of local orchestras, who largely looked to syndicated radio and the national music industry for inspiration. As a contemporary poll in Billboard demonstrates, the University of Texas had become one of the biggest venues for dance orchestras in the country by the early 1940s. Putting on close to 100 concerts in 1942, UT not only far outpaced all other single institutions of higher education, but it put on around 20% more dances than all the universities in California and Pennsylvania combined.

Although the University of Texas was only one of four colleges in Austin in the 1930s, it commanded the most resources. Its cultural and financial draw were, in fact, considerably greater than the rest of the city as a whole, giving it an outsized influence on Austin’s cultural character in the 1930s. UT students—perhaps because they were young elites self-consciously aware of being in what others considered a backwater—tended to favor the most “sophisticated” styles offered by the popular music industry, not regional music made by non-professional or working-class musicians.6 Consequently, music in the Texas capital was decidedly more mainstream and outward-looking than any other city in the state during this period.

UT was not all of Austin, however. The city's segregated African American colleges, Samuel Huston and Tillotson, formed a rich, if largely separate, musical environment. Judging from the available sources, Black undergraduates’ popular music taste was similar to their white counterparts—they favored large bands that played the cutting-edge swing music at the center of the music industry in the second half of the 1930s. Many of the region’s African American dance bands, in fact, were linked to local colleges, like the Sam Huston Swingsters and the Prairie View Collegians.

Austin’s place as a major center for African American higher education in the Southwest in the 1930s also attracted some of the most innovative, successful, and respected orchestras in the country to East Austin. The Cotton Club on East 11th Street, which served as a dance venue for Samuel Huston and Tillotson students, hosted some of the era’s premier touring bands, including Jimmie Lunceford, Earl Hines, Louis Armstrong, Don Redman, and Lionel Hampton. During a portion of his 1936 tour, Duke Ellington stayed for five days in East Austin, where he had friends amongst the local faculty. Although his band didn’t perform at the Cotton Club, he made numerous appearances at important black civic institutions, including talks and solo/duet performances at Tillotson College, the Samuel Huston College Chapel, the Metropolitan AME Church, and Kealing Middle School.

If Austin’s preference for big band music in the 1930s and early 1940s deeply linked it to the central styles of the Depression-era market, the appearance of new local venues, sounds, and audiences between 1942 and 1950 kept it in sync with contemporary shifts in American musical life. The thrifty pre-war years were a time of market consolidation and an emphasis on styles with wide-appeal, namely pop-oriented big bands and dance music. The post-war music market, on the other hand, fragmented into an array of cutting-edge genres, small record companies, and demo-geographically-specific audiences. This was a moment of radical creativity by the pioneers of bebop, R&B, modern country and western, Chicago electric blues, conjunto and the independent labels—like Prestige, Atlantic, Starday, Chess, and Ideál—who recorded them.

Local Memory’s second exhibit, “The Wild Side of Life: The Rise of the Honky Tonks, 1940-1950,” traces the growth of the dance halls, musicians, and audiences that fostered this music in Austin. Venues like the Skyline Ballroom and the Victory Grill primarily catered to working class dancers and featured emerging styles of pop music often deemed unsophisticated or primitive by culturally aspiring students. Breaking with the previous two decades, these spaces and dancers supported a whole new generation of musicians in Austin, dramatically expanding the kinds of music played in public.

The honky-tonk scene exemplified this departure. By the second half of the 1940s, a rim of rough and tumble venues—memorably called “skull orchards” at the time—lay just beyond Austin’s city limits. These clubs provided a home for the burgeoning sounds of electrified post-war country music and Western swing, music that previously had been peripheral to the commercial concert life of the city. Austin’s hinterlands became a magnet for local acts and country and western groups from the surrounding counties, including hit-making artists like Hank Thompson and Jimmy Heap. These venues were soon plugged into the national circuit. They consistently drew major touring stars from California and the newly minted country capital in Nashville throughout the 1950s.

From the beginning, these halls were decidedly part of the town, not the gown. Initially fueled by GIs on leave from the newly built Camps Swift and Hood, these threadbare segregated halls became permanent venues for the area’s white working-class musicians and audiences. Ultimately, these honky tonks, along with analogous clubs in East Austin, created alternative worlds for live music, challenging the power long exerted by the universities and colleges over the sounds of the city.

At the same time, the honky tonk era maintained an important continuity with the big band scene of the 1930s. Like its predecessor, the post-war music scene kept Austin well attuned to the national culture industry, which was in a process of deep diversification. Again, the city did not revolt against mainstream trends but closely followed them. Ironically, keeping pace with patterns driven by other parts of the country made Austin more closely resemble the rest of Texas, which had long fostered a diversity of innovative regional styles.

It was only in the late 1960s and early 1970s that Austin began to turn itself into a haven for less-commercial, progressive, and counter-cultural music. That outsider identity is now likely in retreat, however. As the city becomes increasingly expensive—rents, for example, rose a remarkable 40% in 20217—the relatively cheap and arty environment that undergirded Doug Sahm’s “Groover’s Paradise” and Richard Linklater’s Slacker is disappearing. For all its future-oriented claims, the tech industry has seemingly returned Austin to the past, renovating and flipping the capital into a big-city version of the elite mainstream culture of its interwar period.

But that is just where our story is at the moment. As an open work in progress, Local Memory will continue to expand and be revised over time. The site, in this sense, is meant to stay in media res. We hope that additions to the current exhibits—like upcoming pieces on the Bright and Early Choir, Lavada Durst (Dr. Hepcat), and radio in Austin—will broaden and add nuance to our historical portrait. New themes and research may also modify the work already posted. Our next exhibit on Folklore, Folk Music Collecting, and the Folk and Blues Revival between 1930 and 1970, for example, will show another side of university music culture and its relationship to other Austinites. Stay tuned.

Notes

- This article is a revised version of “Local Memory: Telling Austin's Music History,” Not Even Past, September 1, 2022. I am grateful to Not Even Past for their permission to reprint this article.

- Brian Jones and Michael Schmidt, “The Appendix, Appendixed,” The Appendix 1, No. 3 (July 2013).

- See posts on Michael Corcoran's website like “She's the Boss: Dolores and the Blue Bonnet Boys” and “East Side Stories” and Margaret Moser's work for the Austin Chronicle, especially “Bright Lights, Inner City: When Austin's Eastside music was lit up like Broadway” and “Keeping Up with the Joneses: A Way of Like Compressed into Two Lives.” Richard Zelade, Austin in the Jazz Age (Charleston: Thge History Press, 2015). Beyond published work, institutions like the Texas Music Museum and now defunct Austin Music Memorial have done much to document and commemorate a wide range of music in Austin.

- For an example of how Austin's identity is deeply associated with the music and culture of the 1970s, see John T. Davis's Austin Monthly article “How the 1970s defined Austin.” The major exceptions to this timeline are the early folk career of Janis Joplin and the psychedelic scene revolving around the 13th Floor Elevators and the Vulcan Gas Company. These counterexamples comfortably fit as predecessors to the ethos and style of what came after them, however.

- To understand the growth of the progressive country and counterculture scene in Austin and its relationship to the image of the Texan, see Jason Mellard, Progressive Country: How the 1970s Transformed the Texas in Popular Culture (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2013).

- For example, Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys – whose Western Swing was massively popular with working class audiences in Texas, California, and the Southwest during this period – never played on campus.

- Abha Battarai, “Rents are up more than 30 percent in some cities, forcing millions to find another place to live,” Washington Post, January 30, 2022.